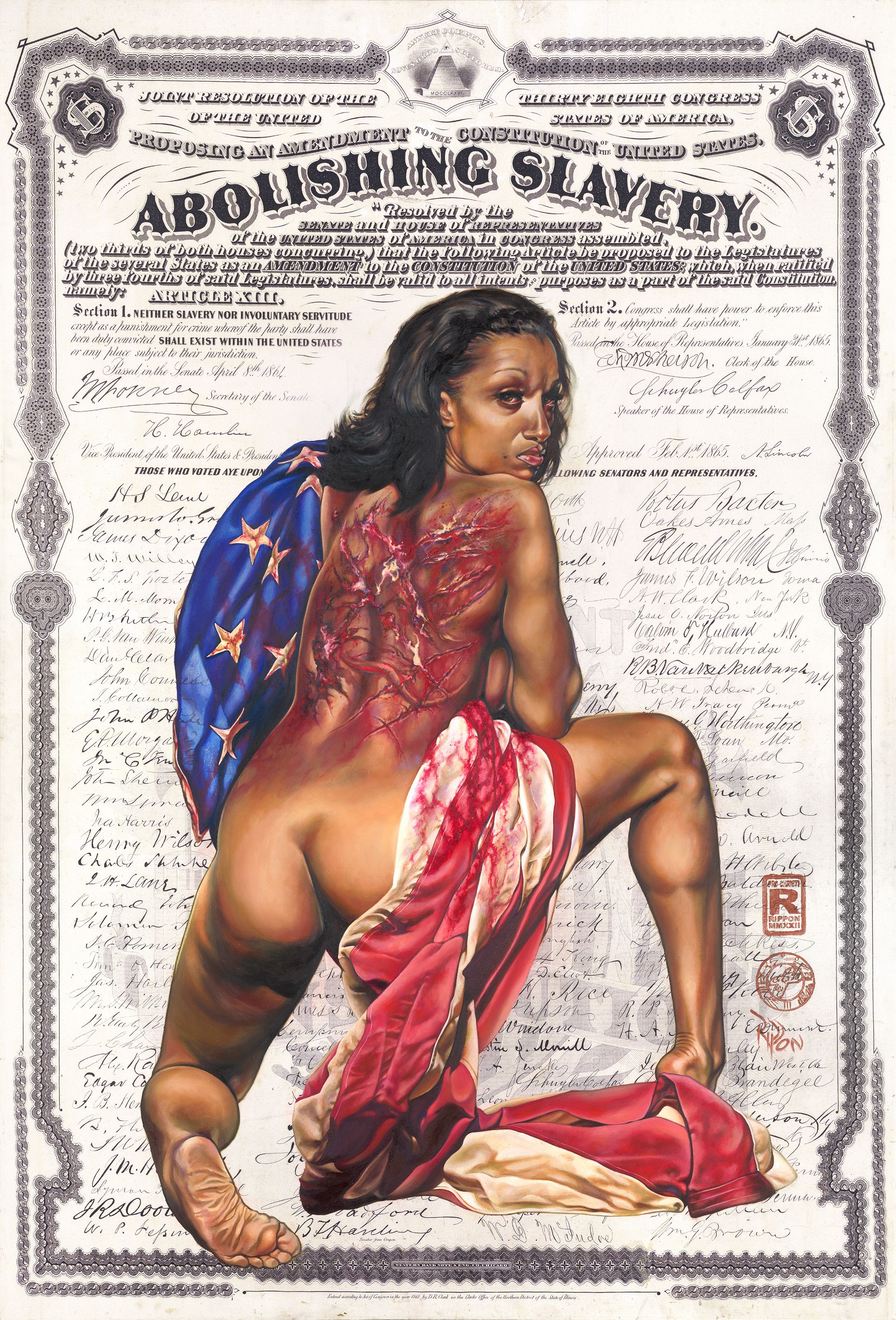

I AM CRT

Craig Rippon

Oil and digital on canvas

195.58cm x 4.41667cm (6’.5 x 53”)

The Parable of Bélizaire

Parable: a simple story used to illustrate a moral or spiritual lesson.

Mike Wallace interviewed Morgan Freeman on the American television show 60 Minutes several years ago. During the interview, Mike and Morgan made their way around to the subject of Black History Month. Morgan was insulted by the idea of the history of Black people being relegated to a month, Black history was American history and should not need any special designation to learn about it. After his cringe-worthy perspective and obvious ignorance of institutional neglect within the American educational system, the conversation moved onto racism. When Mike Wallace asked Morgan how he thought the problem of racism could be overcome, the man who played God responded with “insight” that made it clear to me he was nowhere near God in wisdom or intellect and said, “Stop talking about it.” Please allow me a moment to shudder at the ignorance on display as I wonder if Easy Reader has ever read an African-American history book. Black History Month aimed to raise awareness at a time when notable African Americans were erased from relevance in school history lessons. What became Black History Month started in 1926 as a single week, then grew into a full month in 1970.

While I agree with Morgan that African-American history is American history, beyond that singular truth, I cannot, in good conscience, assent to his subsequent conclusions regarding race and racism. The pushback against CRT confirms many Americans’ desires to cherry-pick historical facts in lieu of full transparency regarding its past and how that past resonates today. Beyond the extremely few historical contributions made by Black people showcased during Black History Month (February, the shortest month of the year, insert Martin Luther King Jr. here), the history of Black Americans highlights a structure of institutional neglect in our education system. Those individuals who Confuse peace with quiet seem to want to sweep the historically infamous deeds of the past away as much as possible. Regarding Morgan’s solution to racism, I am reminded of the late James Baldwin, a man whose thoughts on systemic racism come to mind: “Not everything that is faced can be changed. But nothing can be changed until it is faced.” For Morgan’s myopic solution to hold any weight in this world, society would have to agree that we should all be treated with the dignity God afforded humanity at its creation. Unfortunately, the world is still a long way from the enlightenment that such a solution would require; the erasure of Black people and their contributions to this country throughout American history is obvious. It is for these reasons that concerning African-American parents, I am an advocate of home-schooling if possible.

Bélizaire was a slave who lived during the 19th century, his image can be seen at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and is attributed to the leading French portraitist Jacques Guillaume Lucien Amans. The painting, entitled “Bélizaire and the Frey Children” (a family portrait in which Bélizaire is included), tells its own story and illustrates how African-Americans have been represented, underrepresented, or, in the case of Bélizaire, painted over entirely.

Bélizaire was a domestic slave who cared for the children of the Frey household, he was viewed in many respects as a valued member of the family, so much so that he was included with the children in their portrait. The cognitive dissonance of being “valued” as if he were a family member that could be sold away at any time mirrors in some ways the status of many African-Americans, who are valued for what they culturally and sexually provide while simultaneously, in many cases, are marginalized. Much like the portrait of the Frey children, Bélizaire was painted over, and his contributions to the family were erased. However, his spectral outline remains more apparent by its absence and the incongruity in composition that the void created.

Historically, the spectral outlines of people of color in America are ignored or washed over. However, much like the portrait of the Frey children, the African-American historical outline remains. I wonder how Morgan Freeman would have viewed Bélizaire's disappearance and the subsequent acknowledgment of his missing figure from the painting and, thus, from history.

WHY AMERICAN WOMAN: A LYNCHING SERIES

WHY AMERICAN WOMAN: A LYNCHING SERIES

Her body is the canvas, mocha hues, set against her country’s red, white, and blue backdrop, telling our story for generations.

I’ve always been a fan of pin-up art and erotica and have been greatly moved and inspired by the works of artists like Alberto Vargas, Gil Elvgren, and Hajime Sorayama. However, for as long as pin-up has existed as an American art form, few images have focused on Black women, and none of the few illustrations merged historical elements into their compositions. Painting nude or semi-nude women does not interest me in and of itself. Painting “pin-up” art of Black women had to be about more than “Look, white artists do it. I can do it, too.” The traditional phrase “pin-up” and its close relationship to the word “lynching” was too enticing to be ignored. Hence, the series appellation. The word “lynching” redacts the word pin-up in my mind and so is reflected in the series logo. Between the years 1882 and 1968, 3,446 Blacks and 1,297 whites were lynched. Lynching typically involved extreme brutalities such as torture, mutilation, decapitation, immolation, and desecration.

Why a lynching series? What could I possibly be attempting to do? Idealistically, there are several things I hope my series will address. Using the Black female body as a totem for issues that have faced the larger African-American community; hopefully, forcing candid conversations about racial inequities is my intent. The Black woman, having internalized a foreign value system and attempting to imitate her white counterpart, becomes a distortion of herself. Highlighting an appreciation of Black beauty that might manifest in the abandonment of fake fingernails, false eyelashes, and the wearing, weaving, and gluing of hair from other ethnicities onto their heads would be ideal.

Also, I wish to reconsider the cultural origins of presenting the Black woman as “strong and independent,” brimming with a “combative attitude,” and how that stereotype has sometimes benefited and simultaneously harmed her image. The artistic merging of social/political and historical elements and the African-American female form elevates the works beyond pastiche.

Lastly, white men who appreciate the erotic nature of these paintings and are attracted to African-American women should consider these visual offerings an opportunity to experience a reckoning with the social-historical components that combine to make up what they find alluring.

This is the ideological approach to my “pin-up” art and, for me, separates my work from pornography. Truth is the goal; the Black female form is the vehicle by which larger, more complex, honest conversations about race may be sparked.